I’ve never broken a single bone in my body. I’ve never needed a surgery. I’ve never had an illness which required me to stay in a hospital. All statements are still true, but nevertheless,

this is a story of how I ended up in an operation room.

In June 2021 I started a new job at the Department of biomedical engineering at University of Basel. My team is developing a medical robot cutting bones with a laser. An idea worth my favorite sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov. Advantages of using our robot instead of conventional bone surgery tools are: faster healing, less physical effort from the surgeon and possibility of making accurate cuts in any shape. This is what I’m going to write in scientific papers and most likely nobody will question it. However, I physicist, always crave for deeper understanding of the world. How can I write about a surgery based on my knowledge from TV shows? I could read and cite hundreds of scientific papers, but there is nothing more effective than staring into the face of reality. In this case, the reality was a 19-year-old girl enduring a corrective jaw surgery.

Since I’m officially employed by the Faculty of medicine, there are some doctors in my team. Nowadays, Dr. Drusová is patiently waiting for the technological progress to be able to show her healing skills – one day she can reprogram your bionic arm or retrain the AI in your eyes. On my first working day I was promised to get a chance to see a surgery. The idea got stuck in my head. A few months later, I accepted to be a technical coordinator of the project which inevitably came with existential scientific questions. For example: “Our robot is intended to help surgeons. Are we really heading in the right direction with our technology? What’s the attitude of doctors and patients towards medical robots?” So I arranged myself a guided tour by a cranio-maxillo-facial surgeon, my colleague Neha.

I invited colleagues from the laser group to join me. A senior postdoc and my future boss Ferda got excited by the idea. She had considered becoming a doctor before laser physics got her on board. This was going to be a chance to find out whether she made the right choice. None of us faints when we see blood or dead people, so we made a bet who’s more tough.

As Neha recommended me, I watched a few Youtube videos to understand a corrective jaw surgery. Seemed straightforward.

When upper and lower jaw are not correctly aligned, the surgeons cut out a piece of upper/lower jaw, move it back and attach it with clamps. I was ready to go.

The following morning, Neha welcomed me and Ferda inside the University hospital. It was maybe 10:30 am and she’d been at work since 7, as usual. At first she took us to a kitchen to eat some sandwiches. The food helps with not fainting. She really doesn’t want more work with rescuing our bodies out of the operation room. We were joined by a 13-year-old girl Lilly who wants to become a doctor. Her mum is a science communication expert for the hospital. Neha gave us an insight into a doctor’s life – she can eat on command, sleep on command, work crazy long hours, make decisions in a split second. Yes, the doctors are impressive. What surprised me though is that she finds surgeries relaxing! For sure it means that she’s good at her job. Or what if mistakes are not such a big deal as I imagine?

Doctors in the University hospital communicate using very old Nokia phones. The phones can be used only for calls, there is no need for distraction with apps. It’s not easy to find someone in the labyrinth of corridors. I followed Neha, our tour guide, feeling a mixture or excitement and anxiety. We found ourselves in the dressing room. “How much should we take off?” And there we stood – three women in underwear, a bit cold, waiting what happens next. It brought up Ferda’s memories from all-girls high school. We got dressed in sterile single-use clothing and headed towards operation rooms.

Neha’s boss Florian was performing two jaw surgeries on that day. We arrived when one of them was finished. He greeted us with a relaxed expression and immediately suggested: “Would you like to eat something?” We were not hungry anymore. Florian quickly ate a cup of soup and showed us around. The hospital has a qualified personnel to design and 3D print personalized bone implants. Their 3D printer is a beast that needs an hour to warm up. In the beginning, nobody realized how much heat would this machine produce. Not great for a small room with blood samples! Florian left us to get ready for the next surgery.

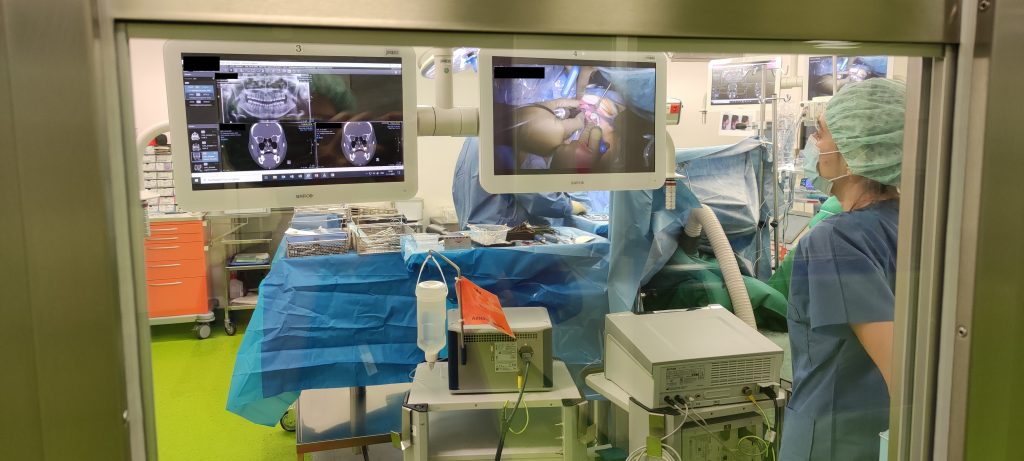

The surgery started. We were allowed to enter the room, less than two meters from the patient’s face. The room was very crowded: doctors, nurses, anesthesiologist and visiting surgeons from Brazil.

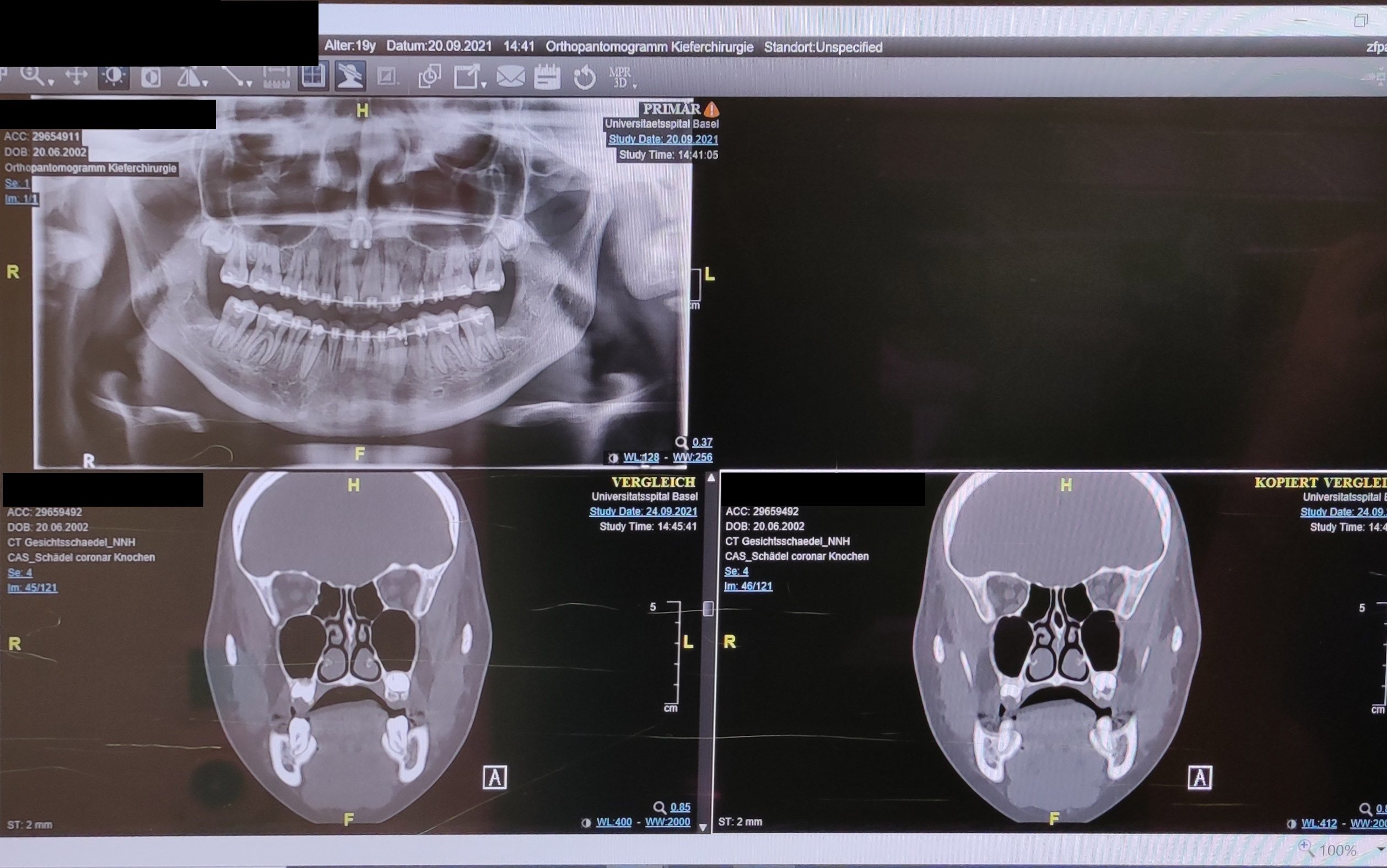

The surgery was filmed and we could watch it live on screens near the patient.

Apart from the surgery, the screens showed X-rays of the patient’s skull and plans for the bone extraction. In order to cut the jaw, one needs to reach it first. Cutting the patient’s cheek is the easiest option, but doctors obviously try not to create an army of Jokers. Instead, they move the skin aside and cut the gums.

Five minutes into the show I started feeling really nauseous. The lights went flickering, my thinking got cloudy and I started sweating profusely. I quickly ran out of the operation room to get less fresh and purified air.

I went to sit next to a toilet bowl just in case I need to see my breakfast again. Everything came so suddenly, there was no specific thought, sound or smell to trigger it in my opinion. It really helped me to be able to take my face mask off. After five minutes of cat videos I completely forgot about previous inconveniences. Lilly also got sick shortly after me. Ferda stayed. Oh damn, Ferda won, she’s more tough than me. Still, I’m a PhD holder and I rarely give up after the first time. I went back into the operation room and kept watching. The doctors were skillfully using burrs, hammers and chisels to crack the skull open. The sounds resembled a dentist’s office which occasionally turned into sculpting. Ten minutes later I got sick again. Went out, calmed down, returned to the room, repeated the cycle. Every time I came back, I could last longer. It was encouraging. I thought: “Whatever makes me sick, I can get used to it!”

The most likely explanation for my reaction is the smell of anticoagulants. I was warned by a robotics colleague who felt the same during a surgery. The room simply smelled clean, but it was a cleanness that I had never smelled before. Luckily there was no barbecue smell.

Ferda had to leave and Lilly was watching from the outside through a glass door. The surgeons used a metal wire looped through braces to fix the patient’s teeth in the correct position. Then they adjusted the shape and size of the jaw cuts. Then attached the jaw with metal clamps. Almost done. As I was feeling more and more comfortable in my role, I started chatting with nurses and anesthesiologists. One of the nurses told me about the patient’s problems and how she ended up in front of us. Teeth grinding was causing her severe pain and she suffered from sleep apnea. The moment I connected the personal story to the face with mouth wide-open, I felt really sick.

I realized that up to that moment, I saw the patient’s body as a malfunctioning machine that had to be repaired.

Once I stopped imagining the patient’s life, what was left was a pure scientific curiosity. It’s utterly fascinating how this invasive procedure can make a body work better.

Lilly concluded that she still wants to become a doctor, but most likely not a surgeon. I concluded that there is still a lot of work to do on our medical robot. Neha invited me for lunch and I gladly accepted. Wow, what an experience! Big thanks to Neha and Florian. I will ask scientific questions some other time…

Here’s a song that got stuck in my head since I came up with the title of this post:

CONTENT WARNING:

Scrolling down reveals pictures that some viewers may find disturbing. Are you curious enough?

Leave a Reply